You are here

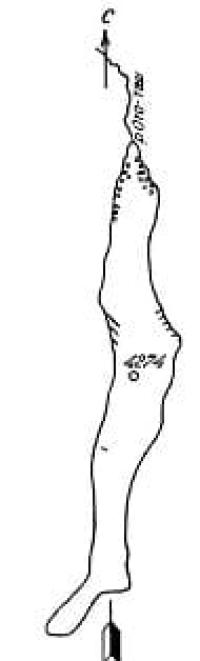

Mushketov Glacier in Kakshaal-Too Range.

N.N. Palgov's expedition to glaciers in Kakshaal-Too Range.

"The second glacier, which I propose naming in honor of the renowned Central Asian explorer D.I. Mushketov, differs sharply in appearance from the previous one. With the same northward exposure and more or less identical orographic conditions, it stretches out in the form of a long, gently meandering ice river with a calm, smooth surface. The glacier was observed from a point on its surface at an altitude of 4,050 meters above sea level."

N.N. Palgov, "Along Central Tien-Shan." 1930.

Research on glaciers on northern slope of Kakshaal-Too Range.

Mushketov Valley Glacier (Oto-Tash, Kotur) No. 251 is located within Kyzyl-Asker mountain range, on northern slope of western Kakshaal-Too Range in upper reaches of Kotur River in At-Bashi District of Naryn Region.

The upper boundary of the glacier is at elevations of 5,038 (Promezhutochny Peak), 4,947 (Kaisky Pass), 4,900 (Studentov Pass), and 4,889 (Pyramid Peak) meters above sea level. The glacier tongue is at an altitude of 4,000 meters above sea level.

The length of Mushketov Glacier (Oto-Tash, Kotur) No. 251 is 9.8 kilometers, the area reaches 12.85 square kilometers, the perimeter is 26.74 kilometers, and the greatest width at the top reaches 1.9 kilometers. To the south, the glacier's headwaters border the East Rudnev Glacier, located on the southern slope of the Kokshaal-Too Range in the Republic of China.

To the west, beyond a 22-kilometer-long spur that merges into the Kagaliachap watershed plateau, lies the East Komarova Glacier (Kyzylunet). To the east lies the 248th Nalivkin Glacier. The Mushketov Glacier is the very first glacier that provides the source of the Kotur River, which in turn is the main source of the Uzengi-Kush River basin.

Expedition by glaciologist N.N. Palgov in 1929.

In the summer of 1929, geographer and glaciologist Nikolai Nikolaevich Palgov led a multi-pronged expedition to the remote areas of the Kakshaal-Too Range, one of the majestic mountain ranges of the Inner Tien-Shan. The goal of the research was to obtain a detailed description of the glaciers, rock formations, and structure of the high-mountain valleys, which until then had remained virtually unexplored.

Palgov and his companions traveled along the northern slope of the western part of the Kakshaal-Too Range, conducting topographic surveys and geomorphological observations. They measured the length and width of glacial tongues - the aforementioned "tsungs" - and noted moraine formations, recharge zones, ice melt rates, and the direction of ice mass movement.

The scientist was the first to systematize data on glacial forms in the western part of the Kakshaal-Too Range, identifying the main types of glaciers: valley glaciers, hanging glaciers, hanging glaciers with branches, and cirque glaciers. His observations formed the basis for the first charts and maps of the region's glaciers.

His field diaries, in which he combined rigorous measurements with surprisingly poetic descriptions, were of particular scientific value:

- "The glacier's tsung, like a frozen stream of light, stretches between black granite. By day, it shines in the sun, at night, it breathes the chill of eternity..."

These words by Palgov became emblematic of a new view of the mountain world, not as a lifeless space, but as a living, moving body of the Earth. Today, many of the glaciers he described almost a century ago have shrunk significantly, but his works remain invaluable evidence of the state of the Tien-Shan at the beginning of the XXth century.

And when XXst-century explorers ascend the Mushketov, Nalivkin, Fersman, and other glaciers, they often mentally return to the lines of his diaries, where each "tsung" was not just an object of study, but the breath of the planet.

Diary entries by N.N. Palgov on his exploration of glaciers on northern slope of western part of Kakshaal-Too Ridge.

"The second glacier, which I propose naming in honor of the renowned Central Asian explorer D. I. Mushketov, is strikingly different in appearance from the previous one. With the same northerly aspect and more or less identical orographic conditions, it stretches out like a long, gently meandering ice river with a calm, smooth surface.

The glacier was surveyed from a point on its field at an altitude of 4050 m. The ascent to the glacier is possible from both the end and the sides. The route is easy, without obstacles. I have never encountered such excellent accessibility anywhere else.

The D. I. Mushketov Glacier stretches for 11.7 kilometers. Its average width is 1 kilometer, and its greatest, in the middle part of its course, is about 1.5 kilometers. The glacier cirque slightly branches to the east and southwest. In the latter direction, it cuts somewhat deeper into the gorge.

The rear wall of the cirque is very steep. It stands out with its dark color, faintly mottled with white spots. Snow, unable to linger on it, falls to the foot, where its accumulated drifts form the glacier's main supply. The lateral mountains, with few exceptions, have fairly gentle slopes (about 30 degrees), and as a result, snow covers them almost completely in thick layers.

Only the steeper slopes, facing southwest, are free of snow. The western slopes, in the area just below the middle reaches, are also free of snow. However, the eastern slopes, in the same area, accompanying the glacier on the left side, bear a number of snow stripes and two fairly thick snowfields.

The general backdrop of the cirque is an almost uninterrupted blanket of white. The outlines of the mountains are generally rounded and soft. Their ridges extend from peak to peak in gradual, undulating curves. There are no sharp discontinuities or breaks, as is typical of the mountain topography near the V. L. Komarov Glacier.

The firn field, as seen through binoculars, was uneven. It descends in narrow, gentle ridges, alternating with equally gently sloping ravines. The surface is clear - no mud or rocks. Near the foothills of the side mountains, small but wide cracks and sinkholes form in places.

As it transitions into the ridge, the average dip angle of the glacier is 3 - 4 degrees. On the ridges, it is greater. The topography of the firn field continues in the same manner on the ridge. Broad, elongated waves extend to the very tip. Initially, their slope is 3 - 4°, and the terraces between them are only 1 – 2°.

However, lower down, the waves steepen and become shorter. The dip angle reaches 5 – 6° and reaches 7°. Despite all this, the relief remains smooth and harmonious. In the middle reaches of the tsung, several narrow, shallow longitudinal cracks are encountered; on the sides, oblique marginal fractures, which merge lower down at the end of the glacier.

Also in the middle reaches, a steep wall is characteristic on the right side. At this point, the glacier, curved like a wave, steeply lifts its coastal limb, producing several wide marginal cracks. At the foot of the cliff cut by these cracks, fallen ice blocks lie.

However, these sharp disruptions in the smooth lines do not affect the overall calm character of the glacier. Lateral moraines are not visible from the surface of the tsung. They are very weakly developed, grouped at the foot of the lateral slopes, and are distinguished by their small height.

Only in the lower reaches do they become somewhat more significant. Here, on the left side of the glacier, the following scene is observed: the steeply dipping slope of the tsung is covered with rocks and rubble reaching the base; then, parallel to the tsung, a narrow, shallow ravine follows, followed by a ridge of older moraine deposits, also insignificant in volume.

A similar scene is observed on the right side of the glacier. Only there, the largest accumulation of moraine material is located at the very end. Below, the glacier's flow is completely free of crevasses. The axis of the flow, noticeable by its swelling, is pressed against the left side.

From here, making a rounded turn, it deviates toward the right bank. Descending gently, the tsung forms a tongue, which at the end becomes thin as a crust. The angle of the glacier on the left side is 7 - 7.5', on the right it is slightly less. Here, the tongue rises above a small, gently sloping hummock near its lateral edge, beyond which it extends, hidden beneath a ridge of moraine material.

A powerful stream flows to the right, accompanied by a weakly developed lateral moraine. The surface of the tongue appears open. Glacial slabs, scattered rocks, and patches of mud do not obscure this impression. Numerous small streams flowing down the tongue form several small lakes.

From there, the water flows out in larger streams, winding between the cones and ridges of the frontal moraine. Ultimately, the predominant mass of water is concentrated in two streams. One is the eastern one, already mentioned above, and the other, less powerful, originates from the western edge of the glacier.

The frontal moraine is 300 - 400 m long and 25 m high. It starts from the end of the tongue with small ridges that have preserved the ice underneath, then turns into a gently sloping platform with a separate "Rock piles." In addition to large fragments, fine clayey material with pebble mantles is prominent in the moraine.

It predominantly covers ridges and cones, giving the latter distinct geometric shapes.Below the new frontal moraine, there are no other terminal moraines in the valley. The river flows in numerous branches along a smooth, pebble-covered channel up to 600 m wide and gently descending at an angle of 1°.

The foot of the frontal moraine is at an elevation of 3,805 m, and the tip of the tongue is at 3,830 m. The area of the glacier, excluding the slopes that feed it, is 11.5 square kilometers. The glacier is not advancing. Since there is no clearly defined ridge in front of its tongue, but rather a series of individual cones, ridges, and accumulations of water in the form of small lakes, it can be assumed that it is not in a stationary position.

It is highly likely that it is currently undergoing a period of retreat, which is reflected in the relatively weak signs of sediment near its end. The glacier provides an excellent object for observing surface velocity, spatial conditions, and so on. Easily accessible and convenient locations for establishing reference points are available everywhere on the coastal ridges of the mountains.

I personally established spatial observations. Measurements were made with a metric tape measure, adjusting the angles of inclination to the horizon, and directions were determined using a simple compass from a plane table, with the inevitable errors involved.

According to the pre-planned program, the observations were to be conducted with a one-minute theodolite, but an unfortunate incident ruined these plans. The theodolite, intended for this purpose, was previously in use by a land surveyor. During one of the observations, a strong gust of wind knocked the instrument and its tripod off.

The fall bent the axis of the limb, resulting in such an eccentricity that even the crudest precision measurements were unacceptable. This unfortunate circumstance forced me to make do with more simplified methods and, moreover, completely abandon the idea of determining glacier velocity.

The Oto-Tash River, flowing from the D. I. Mushketov Glacier, branches into two parts upon entering the Kogalya-Chap Valley. The larger of these branches turns east, where, breaking through the spurs of the Kok-Shaal and Borkoldoy, it flows into the Chon-Uzengush.

The second, smallest, spreads out among the valley's small lakes and, leaving behind its disturbed silt particles, continues westward as a small, clear stream, joining the Aksai basin."

Geographical coordinates of Mushketov (Kotur) Glacier: N41°04'34 E77°26'06

What is "tsung" in works of N.N. Palgov?

In the works of Nikolai Nikolaevich Palgov, dedicated to the exploration of the Tien Shan, the term "tsung" is often encountered - borrowed from the German word Zunge, meaning tongue. This is how Palgov referred to the lower valley part of a glacier, which descends from its firn basin, advances through a gorge, and terminates in a glacial front.

In his 1929 description of the Mushketov Glacier, we read:

- "The main glacier tsung of the Mushketov Glacier extends westward and divides into two branches at its front. Between them lies a moraine ridge composed of blocks and fragments of limestone and shale."

(N.N. Palgov. "Along Central Tien-Shan" 1929.)

Thus, a glacier's tsung is essentially its "tongue," the valley portion carrying the main flow of ice and moraine material. The term was used by Russian geographers in the early XXth century, influenced by the German glaciological school, where similar forms were called Gletscherzunge.

Today, in modern scientific literature, more precise terms are used instead of "tsung":

- glacier tongue,

- glacier ablation zone,

- lower valley portion of the glacier.

An interesting detail:

Palgov not only described the "tsungs" of glaciers but also noted the differences in their shapes and movements. He believed that the shape of the "tsung" reflected the glacier's "temperament" - how actively it moved, melted, and responded to the climate.

This demonstrates his rare talent as an observer: he was able to bring the glacier to life, presenting it as a living being.

Authority:

Palgov, N.N., "Along Central Tien-Shan." 1930.

Alexander Petrov.

Photos by:

Alexander Petrov.