You are here

Kazakh ornament.

Creativity in Kazakh pattern.

“As a saba - my heart.

Wonderful magic kumiss from

souls,

without hiding, without skimping,

I pour into your souls"

"Singer". Ilyas Dzhansugurov.

Kazakh pattern.

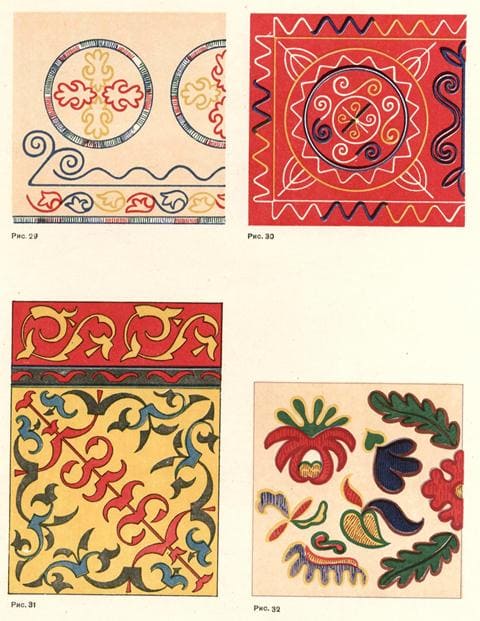

This album of traditional Kazakh folk ornaments is compiled from the drawings of the artist E. A. Klodt, who worked in 1927, 1930, 1934 - 1935 in Kazakhstan, mainly in its northeastern regions. On instructions from the Omsk Museum, E. A. Klodt carefully copied a large series of ornaments typical of northern Kazakhstan.

A comparison with a number of authentic works of Kazakh folk art shows that E. A. Klodt’s sketches are very close to the originals.

E. A. Klodt was not a linguist.

His work on the ornament was not accompanied by research into the folklore meaning of the patterns. Nevertheless, the material he collected is complete and is a valuable contribution to the study of Kazakh art. Until now, we have had almost no publications of Kazakh creativity in color reproductions, except for the publication of individual felts or embroideries, for example, a color table in the collection “Kazakhs” published by the Academy of Sciences (Leningrad, 1930, Table I).

Single-color reproductions of the Kazakh pattern are, of course, inferior. In Kazakh ornament, as in ornamental folk art in general, color plays a very important role. Colorful reproductions of this album can help to widely familiarize ourselves with the creativity of the Kazakh people.

The traditional folk pattern lives and develops in modern Kazakh art, and therefore the album of ornaments will undoubtedly be useful to practical workers - masters of folk art, a growing cadre of artists, those new people of our homeland who know how to simultaneously build Turksib and create works of art.

The folk art of Kazakhstan, beautiful and colorful, has not yet been studied enough. Several small articles, chapters and comments in separate publications are devoted to it, most of which are characterized by a mixture of the Kazakh pattern with the related Kyrgyz one.

It is quite natural that under the conditions of the colonial enslavement of the East in Tsarist Russia there could be no real interest in Kazakh folk art and its aesthetic values. Ethnography dominated the study of culture and art.

A number of the most important issues of Kazakh ornamentation, such as the question of the specific range of Kazakh pattern creation, remained unclear even in the works of such a prominent specialist as S. M. Dudin.

The art of the Kazakh people developed under the conditions of a nomadic way of life and is largely determined by the nature of nomadic production. The emergence of its main types is due to the needs of equipment and decoration of nomadic housing - the yurt, and its furnishings.

This is how the production of carpets, wall felts, felt appliqués, patterned felt bags, covers for wooden chests, etc. developed. Wool processing was specific female labor; carving of metal, wood, stone, and jewelry production usually belonged to men.

Throughout the territory of Kazakhstan, artistic work was already developed to one degree or another before the revolution; a varied range of ornamentation was characteristic of folk art throughout the country. S. M. Dudin and E. R. Shneider in their works, using large expeditionary material, described in detail the variety of types of Kazakh art and the richness of its technical techniques.

A. E. Felkerzamb gives a large number of names for carpets and patterns for felts. Until now, very little linguistic and folklore material has been collected that explains the origin of names and the meaning of patterns, which is so necessary for a detailed study of ornamentation.

But work in this direction is underway. In recent years, the State Central Museum of Kazakhstan in Almaty has collected a collection of patterns from southern Kazakhstan, establishing the folk nomenclature of various artistic products and individual patterns.

Here you can find a wide variety of pattern names already known partly from literature (cited by S. M. Dudin, E. R. Schneider, R. Karutz and others), showing the breadth of the content of ornamentation, the breadth of folk creative imagination: sun, golden eagle, head horses, ram, camel track, tree, ram horn, amulet (tumarsha), saw, bird's palate, golden eagle's paw and many others.

Images of horses and riders are found on tombs made of chalk stone. In the domed Kazakh mausoleums (for example, at the Korkut ata mausoleum on the Syr Darya River, in the Atbasar area, etc.) you can see paintings depicting military campaigns, migrations, and everyday scenes.

These paintings, dating back to the 18th - 19th centuries, are apparently associated with ancient animistic beliefs that were widespread in the nomadic steppe. Kazakh art in its historical past was also known for monumental sculpture, which was associated with the custom of installing statues on burial mounds.

The information that has reached us speaks of the custom of worshiping a statue of a spirit that took place at the end of the 19th century in the northeastern part of the country. In one cave near Semipalatinsk, masses of people flocked to worship a statue depicting a woman in human size.

An essential feature of old Kazakh folk art, which mainly (but, as we have already noted, by no means in general) came down to patterns, is the exceptional harmony of linking the ornament with the form, with the plasticity of the thing being decorated.

The patterns of felts, painted tables, and wood carvings of northeastern Kazakhstan published in this album speak quite convincingly of this. The coloring of things is imbued with great emotionality. In this sense, the Kazakh pattern produces a remarkably joyful, cheerful impression. A. M. Gorky at the All-Union Congress of Writers in 1934 said that:

“Pessimism is completely alien to folklore.”

The great historical experience of artistic work, closely connected with the entire structure of life of the people, created this color and patterned clarity and vigor of Kazakh folk art, determined the love of the Kazakh people for the artistic and aesthetic treatment of all objects surrounding them in life (yurt, costume, etc.).

The latter makes Kazakh art similar to the creativity of other peoples of Central Asia. The variety of types of Kazakh art, the multitude of its patterns, its rich decorative, colorful range left the imprint of genuine nationality on the new art of theatrical and stage design created after the revolution.

Thus, the wonderful production of “Kyz-Zhibek” (“Silk Girl”) by the State Musical Theater of the Kazakh SSR owes much of its success to folk songs and folk patterns. The ability of the Kazakh people to organically translate art into everyday life is extremely valuable. Studying and mastering the high skill of old and modern folk patterns, its harmonious connection with the objective world can give a lot to our applied art.

Professional artists have a lot to learn from folk artists, and first of all, the ability to bring art into public life, holidays, and everyday life. The classics of art learned from the people. Many of the best works of contemporary artists of the Soviet East (Ts. Sampilov, B. Nurali, U. Tansykbaev, U. Japaridze, I. Toidze, N. Chevalkov) are associated with folk art.

The Kazakh pattern is a unique and beautiful page of folk art from the Land of Soviets. The salt marsh steppe is poor in greenery. A herd wanders in the distance. A chain of yurts is drawn against the blue sky. On the milky white background of the patterned felt covering the entrance of the nearest yurt there is a spiral-shaped, horn-like, black ornament.

A similar landscape of the old nomadic camp is repeated. It must be sought in the very world of ornamental forms of Kazakh creativity and patterns. A visitor entering the yurt is struck by the elegance of its decoration. A thin woven strip tightens the wooden frame of a nomadic dwelling, hung with gray-brown unpatterned felts.

Felt and woven bags on the walls, felt mats, carpets, colored covers of carved chests, leather vessels with an embossed pattern, wood carvings - all this can be found in the cool shade of the yurt. There's a pattern everywhere.

It is closely connected with everyday life, with every event in the life of the people. The wedding yurt is hung with large-patterned felts, and the entire home is festively transformed in the shimmer of the ornament. The pattern decorates not only the home and its furnishings, but also the costume of people.

On a woman's headdress (seiküle), a figured silver plate merges with patterned embroidery. In this world of patterns, here and there you find hints of images of reality, of real objects. In the repeated rhythm of carpet rosettes, in decorative images on leather vessels, in brown patterns on woven runners, in massive jewelry you can see the world of reality surrounding the nomad, transformed by folk creative imagination. It is peculiarly poeticized in the pattern.

The question arises: why does the content of old Kazakh art find its expression only in ornamental form with its conventional images and simplicity of decorative formulas? An explanation for this must be sought in the unique setting of the historical development of Kazakh culture.

The artistic work of the Kazakhs in the past was determined mainly by the conditions of the family and clan structure and was only beginning to rise to the level of the craft phase of development. He was associated with nomadic production and was largely subordinate to it.

The production of artistic products still retained the characteristic imprint of socially undivided labor. The creativity of patterns was a product of the artistic activity of the entire people. The forms of artistic knowledge were determined by primitive religious ideas about the world.

It can already be considered established that the ancient principle of patterned decoration of things developed as a result of the fact that folk fantasy ascribed magical meaning to the ornament and considered the depiction of certain patterns a necessary means for the successful development of economic and productive activity.

“Extensive research into the decorative arts in all parts of the world,” writes F. B. Boas, “has proven that decorative design is practically associated with a certain symbolic meaning.” The works of many scientists (M. Verworn, G. Kühn, Fraser), linguistic studies of academician N. Ya. Marr and his school connect the emergence of patterns, ornaments, tamga rosettes, totem signs, etc. with the development of artistic thinking in primitive production , in primitive life.

n Yagnob (mountainous Tajikistan), a woman ceramicist, in order to obtain durable, good products, gives her vessels the conventional features of a human figure. This is an image of the “Feast” - the spirit, patron of production.

A. M. Gorky belongs to the wonderful words spoken at the All-Union Congress of Writers:

- “God was an artistic generalization of the successes of labor, and the “religious” thinking of the working masses must be put in quotation marks, because it was purely artistic creativity.”

In old Kazakh folk art, numerous rosettes and patterns are based on elements depicting the horns of animals, their heads, and their silhouettes. Such patterns can be found on felts, in fabric, in embroidery, in all types of folk art.

onventional images of animals were artistic and magical formulas, spells, and symbols of the success of nomadic production. They were differentiated in color and enriched in decorative compositions with various combinations.

A real phenomenon, understood in its primitive magical “essence,” was doomed to be depicted in a schematic image, in a conventional, fantastic allegorical pattern. This can be seen, for example, in the ornamentation of various Kazakh carpets.

There are carpets with a brownish-terracotta background and high pile. Their middle field is decorated with repeating octagonal rosettes, divided into four segments by straight lines. In each segment, a silhouette “geometricized” figure of an animal is woven. This figure has its prototype in hunting magic; later, at the tribal stage of nomadism, it apparently became a pattern-spell for the fertility of livestock and became more complex in its graphic design.

A similar motif in its original form can be found among the Tavgians (one of the peoples of northeastern Siberia) in the tribal tamgas - “deer of the sun”, in the oval figure of the tamga - “deer of the moon”.

The Olkhon circle of ornaments of Buryat Mongolia already has patterns-spells, patterns-talismans in the form of closed rosettes.

In mountainous Kyrgyzstan, for example, in Susamyr, many ornaments retain clear traces of their industrial significance. This is the pattern of “itkuirugu” - the tail of a Taigan dog (of the greyhound breed), which was used for hunting animals.

At the developed stages of tribal society, that is, with the formation of tribal unions, the range of motives for creating patterns becomes very diverse. Ornamental landscapes are created in which trees, hills, ditches, and herds are depicted; a kind of ornamental sign conveys individual elements of the landscape in a rosette.

These patterns, created by folk imagination, are incantatory formulas associated with the need for water and pastures, without which cattle breeding is unthinkable. Landscape rosettes are found in Kazakh carpets with a red-crimson background, with a slight brown tint.

Patterns with ritual significance are widespread in Kazakh ornamentation: “animal tracks” and “animal horns”. The horn motif appears to be predominant in the decorative patterns of felts and patterned felts, the technique of which Kazakh women raised to great heights.

Essential feature In the decoration of many Kazakh carpets, felts and felts that have come down to us, there is the repetition of one specific figure in rows. In such compositions, we are obviously already dealing with that stage of folk art when, in comparison with the original magical ornamentation, it rose to a higher level of development, despite the fact that each such composition contains many rosettes and patterns that had magical significance.

The late stage of the art of the tribal system still lives in the XVIIIth - XIXth centuries in Kazakh folk art, just as it lived in the ornamentation of Shugnan and Pamir. However, in Kazakhstan during this period, traditionally reproduced ornamental forms in a number of cases already lose their original incantatory, productive meaning.

When many ornamental motifs lost their magical content (often living longer only in their name), then a variety of compositional combinations and decorative colors of these motifs developed, and folk craftsmen had the conditions and opportunities for richer decorated things.

The traditional pattern has turned into a new one in color, into a new composition decorating the figure. This is how “poly” (“flowers”) rosettes were formed in the Turkmen carpet, which initially had nothing in common with a flower.

Pre-revolutionary Kazakh folk art entered that stage of artistic modification of traditional patterns when the harmonious connection between the pattern, shape and plasticity of a thing was fully developed. Complex decorative compositions, especially those that apparently developed in the XVIIIth - XIXth centuries, reflected the great creative and aesthetic culture of the Kazakh people. The Kazakh people created their own unique art of pattern in broad cultural communication with other peoples of Altai, Mongolia, Central Asia, etc.

The close artistic connection and kinship of the Kazakh pattern with Turkmen, Buryat-Mongolian, Tajik, and Kyrgyz ornaments can be easily traced. We also find motifs close to a number of the oldest Kazakh patterns in the Scythian-Altai circle of art.

xcavations in Altai and Oirotia also discovered stylistically very related motifs in ancient carvings and scraps of fabric. The embossed pattern on Kazakh leather vessels, which look like a schematized overturned volute, is a “variant” of the ornamentation of Oirot utensils for milk and dairy products.

A similar relationship is observed in the patterns of Kazakh and Kyrgyz felts. Examples of such parallels are numerous. The creativity of the Kazakh people is based on the patterned creativity of the tribes of Asia and is associated with its general development.

The peoples who inhabited the territory of Kazakhstan before the appearance of the Kazakhs on the historical arena (Scythians, Huns, etc.) left their mark on their artistic culture. Ancient authors, from Herodotus to the Byzantine historian Meander the Protector, tell stories about these peoples.

It is precisely the fact that the Kazakhs inherited the artistic culture of more ancient peoples that explains the successive connection of the art they created with the ancient ornamentation of Northern Mongolia, in particular with the fabrics and woolen carpets of the Noin-Ula mounds.

This conclusion can be reached by comparing the Kazakh pattern on felt with fragments of carpets from Noin-Ula. The unity of the social environment, a certain similarity of natural production conditions, and a close historical connection determined the kinship of Kazakh art with the art of the Kyrgyz and some other peoples of Asia, the similarity of a number of motifs, and the assimilation of some artistic forms.

But this relatedness is not identity.

An extremely harmful point of view, sometimes found in literature, is one that denies the independent historical development of the Kazakh pattern and its folk tradition. This is, for example, the opinion of E.R. Schneider, who believes that “Kazakh ornamentation represents, as it were, one unique and originally developed cross-section of the general Turkish artistic nomadic culture... the roots of this latter came from the Iranian world.”

This is a fundamentally incorrect formulation of the question. Kazakh folk art has its own independent history, its own specific characteristics, and, no matter what broad interactions determined the formation of Kazakh art, its values were created in the organic synthesis and transformation of all these subsoil nutrient juices.

The artistic processing of things in Kazakh folk art is very high. The simplest linear patterns are always saturated with bright and clear colors. The special strength and attractiveness of decorative Kazakh culture is reflected in color.

Precisely because Kazakh art was mainly reduced to pattern, folk artists especially clearly revealed the lyricism and emotionality of their creativity in color, its rhythm, and harmonious color compositions. This can be observed in bau "bashku-rah" - in carpet runners for yurts.

Coloring is never indifferent to the graphic scheme of the pattern. She always highlights the main figures, decorative centers creating an auxiliary color background for them. The pattern appears in fused unity with the thing, its form, its plasticity.

This is especially clearly visible in a suit. On rich festive velvet robes and on women's outerwear, a relief gold embroidery pattern is a decorative link between the material itself and the plates of silver jewelry. On the household items of the former feudal nobility (khans, manaps), the folk diversity of colors is weakened and it is not different colored threads that predominate, but silver and gold thread. The heavy shine of metal falls on velvet, satin, and fabric.

A kind of synthesis in the old Kazakh folk art was carried out in the ornamental treatment of mobile architecture - the yurt, in the close connection of the artistic design of the dwelling with all its furnishings, with all its object inventory.

his synthesis was especially clearly revealed during holidays, joyful events in the life of the people, on the days of baiga (equestrian competitions) and at those moments in the social life of the camp that evoked a desire to decorate the entire environment as best as possible. Then the most beautiful felts were hung in the yurts; people wore patterned suits.

The people who created their art highly valued its significance. Even in the conditions of capitalist tyranny and feudal oppression, working Kazakhs did not lose their primordial attachment to the aesthetic values they created and highly artistic things.

bowl vases with milky white glaze, multi-colored, often very fine, ornamentation reworks the old folk pattern; New compositional expressions are being sought for plant motifs. This good initiative enriches the world of Kazakh patterns.

In Almaty, wall dishes with portraits of V.I. Lenin and I.V. Stalin were made. These dishes are not inferior in artistic quality to ceramic products with portraits of the leaders of the socialist revolution, created by Uzbek folk craftsmen in Tashkent.

The production of decorative dishes with portraits opens a new page in the folk art of Kazakhstan. This production should become massive. It must satisfy the urgent need of the people to have in their traditional forms of art images of those with whom the victories of socialism are inextricably linked.

Images of leaders in the works of folk artists of Kazakhstan have become increasingly common in recent years. The Kazakh master Khasem Imashev beautifully engraved a portrait of V.I. Lenin on silver plates. Kazakhstan is rich in excellent folk craftsmen. In every district of our fraternal union republic, folk artists live and create.

An important task now is to unite them, involve them in creative unions, and provide all possible assistance to them in their work and in their new creativity. Such masters of felt ornamentation as Barlybaeva deserve national recognition.

She raised the tradition of folk art patterns to great heights, decorating a huge felt felt with an original composition, the finest ornament. The Alebaevs compete with her in the production of carpets, in the richness and harmony of the colors of the pattern. In modern Kazakh art there is a struggle to preserve the best traditions of folk patterns.

Mastering the high culture of folk art is an important and significant task facing artists. This task is associated not only with the development of professional art, but also with the creation of new decorative art - this very significant part of the national culture as a whole.

Folk artists are among the first ranks of creators of a new aesthetics of joyful life, because, as V.I. Lenin taught:

“Only with socialism will a rapid, real, truly massive movement forward in all areas of public and personal life begin, with the participation of the majority of the population, and then the entire population.”

Authority and pictures by:

"Kazakh ornament. »Introductory article by V. Chepelev. Sketches by the artist E. A. Klodt. Editor M. L. Neumann. Technical editor E.I. Getz. Artists McRudl and Chikhirish. 1939 Publishing house "Art", Moscow.