You are here

History of village of Lepsi (Lepsinsk).

History of Semirechensk villages.

“A terribly provincial town..., terribly built-up quarters; lonely houses and small groups of wooden buildings, it is so scattered that due to the absence of a church, it is not possible to immediately understand where Lepsinsk itself is. Only the high minaret of the Tatar mosque and the shopping area, built up on three sides with squalid little shops, reminding you that you are already within the city. There are no stone buildings in the city, except for the treasury and the city school; most of the best houses belong to the Tatars... Half a mile from the bazaar, to the east, along the right bank of a mountain river Bulen is a Cossack village with a regular layout of 600 yards. There are many good houses in the village... All the buildings are wooden, not excluding the church, located in the middle of the village. There is a good garden near the church, and trees are planted along the streets near the houses. In general, the village Lepsinskaya makes a favorable impression on a fresh person."

Researcher R. Zakrzhevsky. 1893.

History of Lepsinsky district.

In 1822, the khan's power in the middle zhuz was abolished. Already in 1826, Sultan Syuk Ablaykhanov wrote a petition to annex the Kazakhs of the Wusun clan to Russia. A commission was sent to Semirechye under the leadership of Colonel Shubin, accompanied by a detachment of Cossacks.

Then the question of accession was postponed. Since then, many travelers and researchers have sought to explore this region, but the main task set by the tsarist government - the annexation of the Great Horde to Russia - was solved only in the late 60s of the XIXth century.

In 1837, the grandson of Ablai Khan, Kenesary Kasymov, after the death of his brother and father, again rebelled; the tsarist government took a number of measures to stop the uprising. So in 1840, military engineer Karelin visited Lepsinsk. When Kenesary and his Tulenguts began to threaten Syuk, Ali and Bulen, then, trying to maintain independence from Kenesary, they asked in 1845 to include several clans of the senior zhuz into Russia.

To conclude an agreement in 1846, over 30 representatives of clans gathered in Oy-Dzhailau. To protect them, in April 1846, a picket with two guns was organized, led by officer Bozachinny. The river on which the picket was located began to be called Piketnaya (Biketnaya), and the picket itself became Chubar-Agachsky, because was located in a mixed variegated forest. When drawing up the agreement, Russia was represented by Major General Vishnevsky, the head of the border department in Omsk.

On the Kazakh side - the above-mentioned sultans. The signing of the treaty took place from July 3 to July 5, 1846. After the signing of the agreement, a celebration and baiga took place. The general left, leaving census takers, population and livestock, and 150 Cossacks, who founded the village of Lepsinskaya, which later grew into a town, among them were Viktor Ivackevich, Adolf Yanushkevich.

The relationship between the Cossacks and peasants with the local Kazakhs was not easy.

“The arrival of the Russians in the region,” wrote M. Tynyshpayev, “the Kyrgyz masses, who had previously heard about the order, justice and power of the Russians, greeted, of course, friendly, realizing that the previous constant disasters from endless wars, internal strife and unrest would come to an end "

But very quickly the tsarist authorities and the Cossacks showed who was the master of the situation - questions about land and water use began to escalate. Even at the founding of the Ayaguz fortification, the Cossacks smugly seized the best places for arable farming and haymaking, which caused protest from the Kazakh population.

And later, the allocation of land for Cossack settlements and allotments was carried out in arbitrary quantities and in such a way that they received already cultivated, well-groomed and fertile areas with artificial irrigation.

According to Ivashkevich and Yanushkevich, there were 25 yurts in Bulenka’s summer camp, and there were so many cattle that they drank all the water from Bulenka, and it dried up. In general, the tasks of the Cossacks of the Lepsinsky district, who were part of the independent Semirechensk Cossack army at the base, 9 and 10 regiments of the Siberian army, created by decree of Alexander ΙΙ dated July 13, 1867, were:

- Final assignment of the region to Russia;

- Colonization and development;

- Border security;

- Formation of part of the armed forces in the region of the empire.

The goal of the Lepsinsky Cossacks, in particular, was to guard the state border and control the Uygentas pass leading to China, which was the only passage through the pass of the Lepsinsky district, which was located not far in the mountains from the village of Lepsinsk.

The Cossacks sought to seize as much land as possible, but Sultan Bulen wanted to give the Cossacks land on the right bank of the Bulenka River, but the Cossacks took it with the help of cunning. They presented the Sultan with a huge bull, slaughtered it, and in return asked for land that could be covered with the skins of the bull. Having received such a great gift, Bulen agreed.

While the Sultan was eating beshbarmak, from the presented bull, the Cossacks loosened the skin of the bull onto a thin strap and laid it out on the right bank. Bulen was forced to agree. So the land was divided between the Kazakhs and the Cossacks, the river began to be called Bulenka, i.e. "separator".

The function and name of the river has been preserved to this day. The pickets transported their families, so they formed on the right bank of the Chubar-Agach valley. In 1854, Major Peremyshelsky B.O. (future bailiff of the Great Horde), stationed here the Cossacks of the IXth - Xth regiments of the Siberian Cossack Army.

In the same year, this detachment built the Vernoye fortification. Villages and fortifications were created to protect new lands and Russian citizens from attacks by the Kokand Khanate. Among them was Colonel Kolpakovsky, after the Kokand Kushbegi retreated, 300 families from the Tobolsk province were resettled in Chubar-Agach.

In 1856, in July, Chokan Valikhanov, the first Kazakh ethnographer and researcher of the country, visited here. 1857 became the year of P.P. Semenov-Tien-Shansky. At that time there were over 2000 people in the village. It was on his advice that bees were brought from Altai.

Subsequently, there were 43 apiaries on the territory of Lepsinsky district; in terms of honey yield and quality of honey, Lepsinsky honey ranks 2nd after the East Kazakhstan region. Lepsinsky honey was exhibited at exhibitions in Moscow and won repeated gold medals. A shop was opened in Moscow that sold only honey brought from Lepsinsk.

In Lepsinsky district before the revolution, the main points of concentration of bees were the city of Lepsinsk and the village of Lepsinskaya. According to the chronicle of Russian beekeeping compiled by V.P. Popov

In 1848, beekeeping in Semirechye first appeared in the vicinity of Lepsinsk, and from here it spread to other parts of it (1848 - 1850). In order to avoid confusion in the names of new villages and villages (there was already Chubar-Agach in the Semipalatinsk region, Uygentas in the Kopal district) - the village was renamed Verkhne-Lepsinskaya.

After the abolition of serfdom in Russia, a massive resettlement of peasants began from the central regions of the empire to its outskirts. Kolpakovsky, by that time he had already become a general, developed rules for the resettlement of peasants in Semirechye in 1886, which were in force until 1891.

The settlers received 30 dessiatines per man and were exempt from duties for 15 years; they were given 100 rubles as allowances. In 1880, Lepsinsk received the status of a county town with a population of about 20,000. According to the 1897 census, there were 17 purely peasant villages in Lepsinsk county.

At the same time, the resettlement of the Tatars began. A new wave of immigrants began in 1906 during the Stolypin agrarian reform. Over the course of 4 years, 4 million dessiatines of land were confiscated in the Dzhetysu province in favor of settlers from Voronezh and Poltava and other regions of Russia.

The city of Lepsinsk and the Lepsinsky district were led by Fedorov (1904 - 1906), and the office of settlers was led by Colonel Andreevsky. The lands of the Kazakhs were transferred to the settlers. Moreover, they took away the best lands and pastures, pushing the Kazakhs into the Balkhash steppes.

Thus, the colonization of Kazakh lands took place. In 1910, there were 17 volosts in Lepsinsky district. The head of a clan or sub-clan was usually appointed volost. In the same year, beekeeper Klimenko built a building for a school, where a higher elementary school was opened.

There was a parochial school, and a Tatar school was functioning at the mosque, where Latypov’s teachers were specially sent from Kazan. In the county town there was a distillery, two breweries, two water mills and a wax factory, and 14 taverns. The owners were Pugasov, the Poshivkin brothers, Shkurenko, Beibit Kulbayev, and Portnykh.

In 1913, the coat of arms of Lepsinsk was approved: against the backdrop of mountains - the head of a deer, below on a green carpet of grass - three golden beehives. It was not for nothing that Lepsinsky beekeepers Mironenko, Vasilenko, Klimenko and others sent a barrel of fragrant Lepsinsky honey to St. Petersburg for the 300th anniversary of the House of Romanov.

The First World War, which began in 1914, did not pass by the Lepsin residents. Many Cossacks of the Semirechensky regiment were sent to the front. Belyanin Ivan Lavrentievich distinguished himself there - Full Knight of St. George, rose to the rank of colonel; Berdnikov, Kalinin, Osipov and many others.

The indigenous population was not taken to the front; due to the protracted war and large losses at the front, in 1916, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia adopted a decree on the involvement of civilians in rear work, which caused a wave of popular indignation.

And in 1916, performances took place that swept through the volosts of the Lepsinsky district. The turn of the broad working masses towards the Bolsheviks was clearly manifested in the revolutionary action of the masses of the city of Lepsinsk.

On July 14, 1917, a meeting of vacationing soldiers who arrived from revolutionary Petrograd was organized in Lepsinsk. Bolshevik soldiers who were on leave, Degtyarev and Cherkashin, spoke at the rally, calling on the soldiers to refuse to join the teams, denying the legality of the trial, etc.

These calls were actively supported by soldiers K. Pogozhev and I. Sakharov. On July 15, a mass meeting was held again, where the urban poor and peasants from nearby villages were present along with the soldiers.

The workers at this rally decided to take power into their own hands. A number of decisions were made to improve the situation of the poor and the disarmament of local kulak elements. The rally participants arrested the district commissioner of the Provisional Government, his deputy, the chief of police, the town mayor and tried to disarm the local guard team.

For 8 days the city was at the disposal of the rebels: power in the city passed into the hands of the Control Commission, consisting of Pshenkin, Drobin, Chernov, Dovgalev and others. Due to the fact that the uprising in the city of Lepsinsk was spontaneous and unprepared, it did not find support from the local military forces and broad sections of the peasantry, it turned out to be isolated and defeated.

A punitive detachment arrived in Lepsinsk under the command of Colonel Osipov, arrested members of the Control Commission, and restored local bodies of the Provisional Government. Martial law was introduced in the city, mass raids, searches, arrests were carried out, and the leadership of the movement, Degtyarev and Cherkashin, were brutally killed; while trying to leave for the city of Verny along the ring road, they were hacked to death on the bank of Tentek near Gerasimovka.

The Lepsin uprising of the masses, although it was spontaneous, premature, isolated, showed the growing revolutionary consciousness of the masses, their increased trust in the Bolsheviks and distrust of the Provisional Government.

These events had a revolutionary impact on the entire Semirechye. Unrest in auls and villages intensified, cases of destruction of kulak crops, unauthorized seizures of land by peasants became more frequent, and unrest began among soldiers of local garrisons in Verny, Bishkek, and Tokmak. Soviet power was again proclaimed in Lepsinsky district in early April 1918, when the district congress of Soviets began its work.

The Lepsinsky district congress of Soviets was held under the leadership of instructors sent by the Vernensky Bolsheviks, with the task of explaining the decree of Soviet power throughout the district. Members of the revolutionary regional committee - Bolsheviks Karlov and Silin - were sent to the town of Lepsinsk.

At the congress, the issue of recognition of Soviet power and the adoption of the decree “On Land” was decided. The composition of the congress was heterogeneous, the work of the congress took place in very difficult conditions.

The congress delegates included representatives of kulaks, officials, merchants, Alash Horde members, Socialist Revolutionaries, etc. But mainly at the congress the struggle was between two groups: the first expressed the interests of the bais, kulaks, and wealthy Cossacks, led by the bais Niyazov, Kuderbekov, Shebalin and others.

The second group expressed the interests of the poorest segments of the population of the county - mainly there were delegates from Cherkassk, Petropavlovka, Antonovka and other peasant villages, at its head were Voevodin, Kornitsky, Seredin, Karlov, Zenin, Podshivalov.

After lengthy and heated debates, the congress, by a majority vote, decided on recognition of Soviet power and the decree “On Land”. At this congress, the first composition of the Lepsin executive committee was elected,

Voevodin was chosen as chairman, Dovgalev, Podshivalov, Dovbno, Dyachenko, Karnitsky, Seredin, Lopatin, Karlova, Silin, Zenin, Sobolev, Gorbunov, Matveev, Kuderbekov, Niyazov, Mametov and others as members.

After the meeting of the executive county committee of the Council, work on Sovietization of the county revived, rural councils began to be created and even in the Cossack villages - Topolevskaya, Sarkandskaya, Sergipolskaya. The work of the Soviets of Peasant Deputies was organized in a new way.

By mid-1918, the creation of Soviet governing bodies in Lepsinsky district was completed.

1918 April 14.

Decree of the Council of People's Commissars of Lepsinsky district.

The district congress, having closed its meetings to revise the administration, recognized Soviet power in full, elected a permanent council of People's Commissars consisting of 20 members, which, upon taking office, calls on the entire population of the district, without division of nationalities and classes, to maintain complete order and tranquility. The new government - the power of the people, which guards the interests of the working people is the highest authority in the district and in the event of violence and injustice will be suppressed with the most decisive measures.

Chairman of the Voevodin Council.

On July 22, the executive committee mobilized peasants to fight the Cossacks. Thus began the civil war. City Manager S.S. Podshivalov decided to leave Lepsinsk. At first, members of the executive committee went to Pokatilovka, but there Shcherbakov’s detachment surrounded them and they were forced to move to the village of Cherkasskoe, where from September 1918 to October 1919 (399 days) they fought with the troops of Ataman Annenkov and General Shcherbakov, whose headquarters were for some time in Lepsinsk.

During the deployment of offensive operations of the counter-revolution, the task was to prevent the connection of the counter-revolution and the Siberian and Central Asian intervention. Preserve Semirechye as the most important strategic point, covering Soviet Turkestan from the north from the blow of the Siberian counter-revolution and thereby providing the opportunity to use the military forces of Turkestan in other directions: in the Trans-Caspian region - against the British invaders, on the Aktobe and Fergana fronts.

Economically, it was important for the Soviet command to retain Semirechye as the main supplier of grain for Soviet Turkestan, at a time when it was cut off from Central Russia. Already in the summer of 1918, the counter-revolutionary government of Siberia took measures to capture the Soviet Semirechye.

He was actively supported by the White Cossacks, kulaks, bais and clergy, who intensified their activities hostile to Soviet power. To repel the White Cossacks, to strengthen Soviet power in the region, the Soviet of Deputies began to create Red Guard detachments: in Lepsinsky district, such detachments were organized voluntarily from peasants, front-line soldiers in the town of Lepsinsk, in the villages of Pokatilovsky, Pokrovsky, Aurorovka, Svobodinsky and others, which later became part of Cherkasy defense. The number of Red Guards in these detachments was not constant.

In the village of Pokatilovsky there were 130 armed Red Guards under the command of Poluyanov. In the Lepsinsky detachment of 60 people, only 36 were armed with rifles, the detachment was commanded by Belozerov.

In the village of Avrorovka, the detachment consisted of about 50 people. The Lepsinsky district Soviet of Deputies led a decisive struggle against the counter-revolutionary measures of the wealthy Cossacks, who, relying on the military Cossack circle, were preparing an uprising against Soviet power.

The illegal White Cossack congress, which met in Lepsinsk, openly spoke out against Soviet power and decided to mobilize youth to fight the Soviets. At the congress, representatives of the working Cossacks - Veniamin Tolmachev, Nikanor Bessonov, Ilya Ludin, Alexey Osipov, Peter Pankin, and others - spoke out against the counter-revolutionary measures of the wealthy white Cossacks, and they were supported by the Lepsinsky District Council.

As a result, the White-Cossack congress was dispersed. Thus, the attempt to organize an open protest against Soviet power ended in failure. Then the White Cossacks began to secretly prepare a counter-revolutionary uprising simultaneously in several Cossack villages, encircling the Soviet peasant villages.

Preparations for the rebellion were carried out directly with the knowledge and support of the British, who kept in touch with the White Cossacks through the former Tsarist consul in Western China. Back in April 1918, at a secret meeting of members of the dissolved military council of the Semirechensk Cossack army, a plan for a counter-revolutionary rebellion was developed.

In the Cossack village of Kapal, a “Combat Council” was organized, which began forming White Guard detachments. At the end of July 1918, a White Cossack uprising broke out in the village of Sarkand. The village Soviet of Deputies was dispersed, its members were executed, and 200 Soviet-minded peasants were brutally hacked to death.

At the same time, counter-revolutionary riots broke out in the Cossack villages of Kapal, Ak-Su, Abakumovskaya, and Topolevskaya. The White Cossack rebellion did not break out by chance; it was timed to coincide with the rebellion of the White Czechs in the north of Kazakhstan and the beginning of the offensive of the White Guard troops from Semipalatinsk to Semirechye.

On June 23, 1918, a Red Guard detachment under the command of A. Mamontov arrived in Lepsinsk. This detachment covered the entire Lepsinsky district in three months, clearing the village of white Cossacks and restoring Soviet power, confiscating property from former opponents.

The residents of Lepsinsk began to build a new life: artels were created - “Lepsinsk”, “Semirechenskaya”, “North Star”; collective farms - “International”, named after Kalinin, named after the 16th Party Congress. The State Bank and Sberkassa began their work.

On January 17, 1928, Lepsinsky district was liquidated. In 1931, in the Dzhetysu region there was an uprising in Kapal, Kyzyl-Agach. People fled from barbaric collectivization, which broke out as a result of famine, and fled through the mountains to China.

Border guard Sevastyan Krivoshein stood in their way and was killed in battle. Five years later, the youth of Lepsinsk erected a monument to him and other border guards in the town garden. After the famine of 1931 - 1932, refugees from the Chubartau district of the Semipalatinsk region appeared in Lepsinsk.

People, driven by hunger and cold, moved from place to place in search of a better life, but many of them found it by going to another world. As a result of the famine of 1921-1922, the demographic situation in the nomadic and semi-nomadic regions of the republic was greatly shaken, and in 1931-1932 it became even more complicated.

In the 1930s, during collectivization and dispossession, people's livestock, houses, apiaries, and personal property were taken away free of charge. So, during the process of dispossession of my grandfather Abliev Gumar, they took away his apiary, 2 horses, 2 cows, house and household utensils, and his family, consisting of 12 souls, was kicked out onto the street.

My grandfather had his income from an apiary, and in winter he was a watchmaker. As a memory of that terrible time, my grandfather’s watch hung on the post office and had his initials. This happened to all more or less wealthy families.

The destinies of these people were controlled by former parasites, poorly educated, envious, narrow-minded people. This is evidenced by the fact that the round dining table, taken from the Abliev family, lay all winter in the yard of the Village Council and was cracked from time to time.

In general, from the day of its foundation and in subsequent times, the population of Lepsinsk was engaged in beekeeping, cattle breeding and trade. Market day was held on Friday, which attracted people from Semipalatinsk, Sergiopol, and China.

The regimental brass band played in the city garden. In 1933, a pedagogical school was opened in Lepsinsk. Many teachers graduated from it before 1953, and then it was transferred to Panfilov. A Library College was opened on the basis of the pedagogical college, but it was transferred in 1967 to Kaskelen.

After the adoption of the Stalinist Constitution in 1936, Lepsinsk received the status of a village, many houses were taken to Andreeva. This had an adverse effect on the development of Lepsinsk, because the district center was moved to Andreevka, which was located 45 kilometers from the former district town.

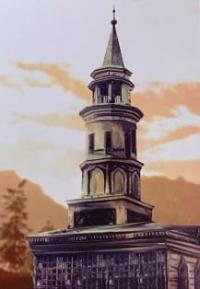

And all the main routes ran away from Lepsinsk. In the same year, a mosque in Lepsinsk was blown up and the bells were thrown off the church. On the large bell it was written: “Smelted at the Ural Demidov plant”; it weighed 125 poods 25 pounds.

The church itself was built according to the design of the famous architect Zenkov, who built the church in Almaty. The building of the church itself was abandoned, and after the revolution it did not function. In 1934, the first inter-district pioneer camp was opened in the church building.

During the Great Patriotic War, a tungsten mine was opened on the territory of Lepsinsk, the products of which were used to produce armor for tanks. The distillery supplied its products to the front. During the war, as throughout the country, the majority of those who remained in Lepsinsk were women and teenagers who did housework.

All the hardships and hardships fell on their shoulders. During the Great Patriotic War, many village boys went to the front, but most of them never returned. At the moment, only four participants in the Great Patriotic War live in the village. The Chairman of the Council of War Veterans is Tokpaev Shayakhmet Shaimordanovich.

The post-war structure of Lepsinsk took place gradually.

In 1957, the Lepsinsky state farm was formed; it had 4 departments:

- 1st department – Zhunzhurek,

- 2nd department – Baizerek,

- 3rd department – Lepsinsk,

- 4th department - Golubev constipation.

Then the state farm was transformed into the Lepsy association. In August 1961, the forestry enterprise was organized, the first director was Petr Vasilievich Maslov. In 1959, the village already had five telephones and 150 radio points.

In the sixties, a water supply system was laid in Lepsinsk and at the end of the sixties the village was fully electrified.

Authority:

http://www.lepsinsk.kz/history/

Photos by:

from Lepsi village museum.