You are here

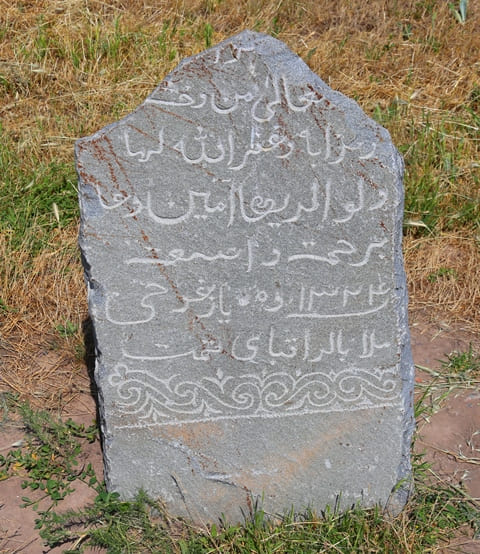

Epigraphy at Burana settlement.

Individual tours in Kyrgyzstan.

"A certain traveler, a Kashgarian, during the compilation of this book in Balkh, said: "Once the ruler of Kashgar invaded Mogolistan to condemn and punish the Kalmyks... they reached some area where from under the sand... the roofs of tall buildings protruded: minarets (underlined by me - V.N.), palaces, arches of madrassas... the captives were asked the name of this area. They said: we know (only) that here (in the past) there was a city called Balasagun."

Balkh historian Mahmud ibn Wali. "Bahr al-asrar fi manakib al-akhyar" ("The Sea of Secrets Regarding Virtues of the Noble" or "Sea of Secrets Regarding High Qualities of Virtuous People". 1634 - 1640

"... In country of Chu, in one place, there are traces of a large city; its minarets, gumbeses and madrassas have been preserved in some places. Since no one knows the name of this city, the Mongols call it Monara...".

Muhammad Haider Mirza, XVIth century.

Exclusive tours in Kyrgyzstan.

Nestorian, Muslim cemeteries and epigraphy in Issyk-Kul region.

The discovery of tombstones with medieval Turkic, Arabic and Tibetan inscriptions in Issyk-Kul caused a wide response in the circles of Russian orientalists. During a trip to the Issyk-Kul region, D. L. Ivanov discovered an ancient cemetery, next to which there was a Kyrgyz mosque.

Following him, F. V. Poyarkov also visited there. On most of the gravestones, signs or inscriptions were carved in a semi-Kufic script. The mullah of the mosque demolished several dozen gravestones with inscriptions and installed them along the walls of the mosque.

D. L. Ivanov took pictures of some of the inscriptions and included them in his publication. According to the mullah, the most interesting stone, on which stood the date 675 AH, i.e. the first half of the XIIth century, was taken to Karakol by the district chief Kurkovsky.

Its further fate is unknown. During his trip to Issyk-Kul, F. V. Poyarkov also discovered stones with inscriptions in the Ton River valley. All of them were piled in one pile, as the author assumed, on one grave. In all likelihood, they had been brought here by someone earlier.

He immediately he handed over some for study to the Archaeological Commission, the rest were sent by him later, in 1891, to the Asian Museum of the Academy of Sciences. F. V. Poyarkov had previously encountered similar stones with inscriptions near the Aksu River on the northern shore of Issyk-Kul and near the Cholpon-Ata station.

The inscriptions were of the Kufi type by their external outlines, but only the reading of the text could finally determine their historical origin. He himself only suggested that the Kayraks belonged to a “Muslim” people, but which one exactly, that’s the question?

The only thing that F. V. Poyarkov asserted more or less confidently was that he had encountered them only in Issyk-Kul, although he had also thoroughly examined the Tokmak district. The same Muslim cemeteries with inscriptions on stones in the Issyk-Kul region were also examined by V. V. Bartold.

He dates them to the XIIth century. In one place near the Aksu River he found up to 70 stones with epitaphs. S. M. Dudin found an inscription on one of the huge stones with niche-shaped depressions in the Ton River valley and copied it. In his opinion, it was carved “not so long ago”, although the Kirghiz claimed the opposite.

Here along the Ton River, S. M. Dudin saw 19 tombstones with “Muslim” sayings. Despite many references to the abundance of similar epitaphs on the southern coast of Issyk-Kul, they are now very rare. At least in the valleys of the Ton and Tura-Su rivers we have not found a single such kayrak.

True, on a rock, at an inaccessible height, the same inscription, carved in Arabic script, which V. V. Bartold cites in the appendix to "Report...", In general, little remains of many epigraphic monuments in the Ton River valley. It is noteworthy that along with Muslim epitaphs, a Christian cemetery and tombstones with Nestorian inscriptions were discovered on the southern shore of the lake.

This discovery was made in the summer of 1907 on the Dzhuuka (Zauka) River by N. N. Pantusov, who found two stones with epitaphs. One of them in the Uyghur language, written in the Syriac alphabet, is interesting because it mentions the name of the famous ancient commander Alexander the Great and his father Philip.

Medieval Arabic inscriptions from kayraks most often contained excerpts from the Koran. One of such epitaphs was read by V. V. Bartold from a photograph of a stone sent by D. P. Rozhdestvensky to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences in 1913, having supplied the translation with an indication that similar poetic texts from the Koran are widespread on gravestones in the Issyk-Kul region.

Authority:

N. Kozhemyako, D. F. Vinnik. "Archaeological monuments of the Issyk-Kul region". Publishing house "Ilim". Frunze. 1975.

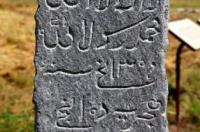

On the territory of the architectural and archaeological complex Burana Tower there are epigraphic monuments in the form of tombstones-steles with inscriptions in the Arabic alphabet. They are dated to the 14th and first half of the 20th centuries. The epigraphic monuments were found in places near the architectural and archaeological complex Burana Tower.

The finds and reading of the epigraphic monuments of Burana caused a great resonance: Syrian-Nestorian tombstones (D. A. Khvolson, P. K. Kokovtsev, S. S. Slutsky) and Arabic inscriptions on kayraks (V. K. Trutovsky): Various information from Arabic, Persian and Turkic sources about Burana and other cities of Semirechye was introduced into science by V. V. Bartold, who visited here in 1893, and N. F. Petrovsky.

Even relatively recently, A. N. Bernshtam wrote that "there are almost no Muslim kayraks in Semirechye." Indeed, medieval tombstones with Arabic and Persian inscriptions, widespread almost everywhere in Central Asia, are very rare north of the Kyrgyz and Zailiysky Alatau.

Against this background, the regular discovery of new stones with epitaphs at the Burana settlement in recent years looks even more impressive and encouraging. In 1983, four of the seven medieval epitaphs in Arabic script from the Chui Valley known at that time were published in the collection "Kyrgyzstan under the Karakhanids."

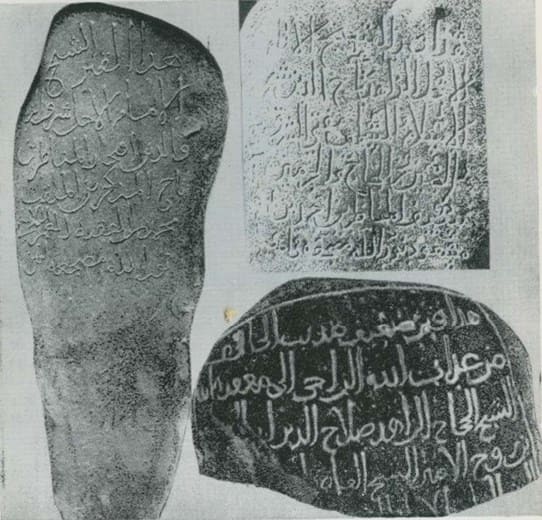

In the proposed article, conceived as a direct continuation of the previous one (preserving the numbering of kayraks begun in it), six more monuments are considered: No. 5 and 6, corresponding to No. 3 and 5 of the edition by Ch. Dzhumagulov; No. 7, from among “about ten kayraks” found by archaeologist D. F. Vinnik in 1970 - 1975.

Published based on a photograph given to me by V. A. Livshits in 1977; No. 8 and 9, discovered in the area of the settlement by local residents in 1982 and 19835; No. 10, discovered by archaeologist L. M. Vedutowa in 1984. In addition, due to the significant bibliographic rarity of the first edition of the Arabic text and the summary nature of this work, a new edition of the text and translation of the epitaph of Muhammad faqih Balasaguni, which has not reached us in the original, is being undertaken here, as it is given in the work of Muhammad Haidar “Ta’rikh-i Rashi-di” (XVIth century).

This epitaph, until the original can be found, has been left without a serial number. Its previous translation has been revised and provided with a subject-philological commentary. Thus, counting the lithographs from two kayraks from Tokmak, published in 1889, today we have the texts of at least thirteen epitaphs in Arabic script from the territory of medieval Balasagun.

The rate of growth of the number of epigraphic monuments allows us to hope that this valuable source on the history of Semirechye will soon be replenished with new finds. Kayrak 5 (according to Dzhumagulov, "monument No. 3"). An oblong rounded boulder of dark gray with a steel tint.

An inscription of 9 lines, the last of which consists of one word. Handwriting - unprofessional early with a strong influence of the Kufi style, simple angular outlines, with rare diacritics: three dots are knocked out under the letter sip in the word al-mastura, the laqab at the beginning of line 6 is completely punctuated.

The graphics of the penultimate line (the name of the inscription artist) are distorted. Without a frame. The epitaph is not dated, according to paleographic data it belongs to the second half of the XIIth century.

1) This is the grave of a magnanimous,

2) chaste, enlightened,

3) righteous, pious,

4) virtuous, highly moral1, Hajjadzhi

5) daughter of Muhammad, - and this (woman) is known, (as) the daughter (?)

6) Butak-Aba (?), may Allah illuminate her bed,

7) may Allah forgive her and (both) her parents!

8) The writer (of this) is her son Nur (?) ad-din, son of

9) Imad.

Kayrak 6 (according to Ch. Djumagulov, "monument no. 5"). Published again based on a photograph and print reproduced in "Epigraphy of Kyrgyzstan". The handwriting of the inscription is late style kufi, in which individual elements of naskh have emerged; visually close to the handwriting of the previous kayrak.

Text of 5 lines without a frame. No date, according to paleography it may date back to the second half of the XIIth century.

1) In the name of Allah, the Merciful, the Compassionate!

2) This is the grave of Mu'alla3, son of Muammad, son of.

3) 'Uthman, son of 'Abd ar-Rahman al-Badakhshani.

4) may Allah have mercy on them [all]! - let it illuminate.

Kairak 7. An elongated flat stone of rectangular outlines with a narrowing at the bottom right. An 8-line inscription in rough late Kufi without diacritics, with strong graphic distortions of individual letters and entire words. The lines are of different heights, not maintained horizontally.

The first line is almost completely knocked down, many words in other places of the text are damaged. There is no date in the inscription, but by all indications the epitaph dates back to the pre-Mongol period. The poor quality and defectiveness of the monument prevent a complete and unambiguous deciphering from the only photograph at my disposal, so the proposed readings and translation of the epitaph should be considered preliminary.

2) 'Umar son of al-Katib (?)

3) enlightener of the readers of the Quran, ... (?)

4) prayed for forgiveness ... (?) of the all-merciful

5) and cast out Satan,

6) and suppressed sins,

7) and illuminated the darkness of his neighbors (?)

8) of expectation (?), may Allah have mercy on him!

I consider the lexical commentary on this inscription, almost all the words of which are understood without complete certainty, to be premature. It seems that the artist of the epitaph not only had a poor command of Arabic writing, but also a poor knowledge of the language in general.

Kayrak 8. A large oval-shaped stone with a "notch" on the left side relative to the inscription gray-pink color with a coffee shade. The inscription in 4 lines in large letters of unusual outlines, without diacritics. The writing style can be defined as an undeveloped early naskh with elements of kufi, in which the influence of the scribe's skill in some other script (perhaps Syriac or Uyghur?) is noticeable.

The text is enclosed in a simple rectangular frame with a diamond-shaped tooth at the top. Found in 1983 on the bank of the Kegety River during the development of a quarry on the territory of a forestry enterprise near the village of Rot-Front.

(1) This is a grave.

(2) Makhir[y].

(3) daughters.

(4) Makhira.

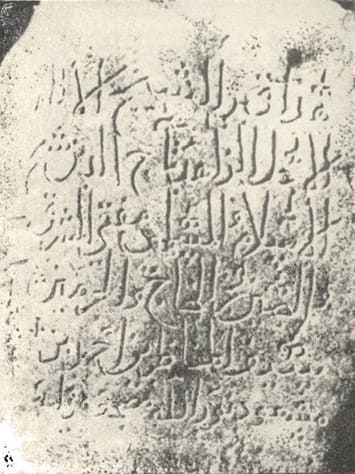

In this regard, the presence of about 20 stones with the text in question in cemeteries on the northern shore of Issyk-Kul (all undated) seems quite remarkable. Against the background of the relative rarity of monuments with the indicated verses of the Koran in other regions of Asia, one gets the impression that for some time their use here was a kind of "local" canon.

Considering the proximity of the Burana settlement to these places, it can be assumed that the origin of Kayrak 10 (and possibly another fragment with a fragment of a similar inscription from the Talas Valley) is also somehow connected with this compact and absolutely isolated territorial group of epitaphs.

Many of them contain the names of the deceased, but there are also anonymous ones (4 stones from the cemetery on the Kungey-Aksu River). Judging by the published photographs, the inscriptions on them are made in Kufic handwriting of an archaic style, many elements of which (medial jim/ha in the form of a slash, dal/zal in the form, sometimes the initial alif with a bend or break from bottom to right and a number of other signs) go back to the paleography of the IXth - XIth centuries.

Reminiscences of early Kufi can also be traced in the inscription from Burana. Taking into account these features, together with the absence of dates, it would be possible to classify all the noted monuments as the earliest Muslim burial grounds not only in Semirechye, but in Central Asia in general.

But the remoteness of this region from the major cultural centers of Maverannahr, its peripheral nature, force us to make a certain allowance for the rate of spread and rooting of the Arabic-written tradition here, as well as its well-known conservatism in relation to lapidary epigraphy.

Hence, taking into account the chronology of the most ancient dated epitaphs in Arabic script from the territory of the Eastern Karakhanid Khaganate, the most acceptable dating of both the Burana Kayrak 10 and its Talas and Issyk-Kul brothers seems to be the second half of the XIth - early XIIth centuries.

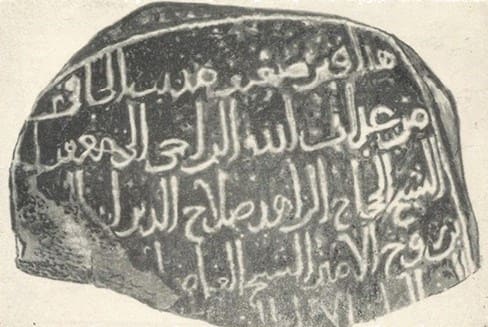

Finally, the newly published epitaph from "Ta'rikh-i Rashidi" testifies to the fact that the city of Balasagun still existed in the first quarter of the XIVth century and traditional Muslim literacy, service to theological sciences, crafts (in particular, blacksmithing and stone cutting) and, obviously, Sufism flourished in it.

The lexical and stylistic features that were standard for that time, discussed above in comparison with other narrative and epigraphic data, may testify in favor of the authenticity of the text written by Muhammad Haidar: it is quite possible that he actually read it in the original and reproduced it with high accuracy (maybe, except for the word sheikh with the missing article, although this could have been the case in the inscription itself.

There are many examples of such errors in Central Asian epigraphy. Of particular interest is the fact that the title khwaja (khodja) is mentioned in the scribe's name, as well as the letters, owner, master; noble/respected person; teacher, etc. This term, of unclear origin (its etymology has not been fully clarified, and its semantics and scope of application have undergone significant changes over the centuries), is relatively rare in Central Asian inscriptions of the XIIth - XIVth centuries and refers to people of various social status and occupations - representatives of authorities, traders, artisans (the blacksmith 'Umar-Khoja' in the epitaph under consideration, the epigraphic nature of which, however, is largely conditional due to the absence of its original.

Without going into a detailed analysis of the meanings and spheres of application of the term in Central Asian anthroponymy, which deserves special study, I will only note that in all cases, including mentions in narrative sources and act documents, this term was applied exclusively to literate, educated people, regardless of their social rank (however, always quite high).

And since literacy here in the first centuries of Islam, naturally, was associated primarily with the Arabic language and the ability to read the Koran, then over time the word khoja began to be understood as a descendant of the Arabs. In conclusion, I consider it useful to note one very curious parallel (although not directly related to the epigraphy), which, in my opinion, could put the final point in the question of the correspondence of the Burana settlement to the medieval Balasagunu.

The testimony of Muhammad Haidar about the area of Dju (the Chu River valley), where the ruins of a large city, called Manara (modern Burana) by the Mughals, have been repeatedly cited in many works by modern researchers. It owes its appearance to the campaigns of the Kashgar troops in Moghulistan against the Kalmyks, Kirghiz and Kazakhs.

The author of "Ta'rikh-i Rashidi", who held a high military post under Sa'id Khan of Kashgar (1514 - 1533), could have been a participant and even the leader of some of these campaigns. One way or another, the information about the ruins of the city, "the name of which no one knows", and about the slab with the inscription, described by him in such detail, was received by him, if not personally as an eyewitness, then at least "first-hand".

A century later, the Balkh historian Mahmud ibn Wali wrote in his work "Bahr al-asrer" about that "a certain traveler, a Kashgarian, during the compilation of this book in Balkh, said: "once the ruler of Kashgar invaded Moghulistan to condemn and punish the Kalmyks... they reached some area where from under the sand... the roofs of tall buildings protruded: minarets (underlined by me - V.N.), palaces, arches of madrassas... the captives were asked the name of this area.

They said: we know (only) that here (in the past) there was a city called Balasagun." The coincidence of the data of "Ta'rikh-i Rashidi" and "Bahr al-asrar" on the main points concerning the description of the remains of an abandoned city in connection with a military campaign (possibly the same one) is obvious enough not to be accidental.

On the other hand, it is precisely the discrepancies in specific details that indicate that there is no direct relationship between these two messages, they go back to different primary sources and were obtained, so to speak, at different information levels.

Moreover, in the entire territory of Northern Kyrgyzstan there is not a single place that corresponds more closely to the descriptions of Muhammad Haidar and Mahmud ibn Wali than the remains of the Burana settlement. From this follows the only conclusion: taking into account the originality and relative independence of the data of both authors, and most importantly - their sufficient reliability, which there is no reason to doubt, we can consider these data one of the most important narrative evidence in favor of the unambiguous and indisputable identity of Burana - Balasagun.

Authority black and white photographs by:

Nastich V.N. "On the epigraphic history of Balasagun" (Analysis of published inscriptions and new finds). Krasnaya Rechka and Burana.

Black and white photograph by:

M.E. Masson. V.D. Goryacheva. "Burana. History of the study of the settlement and its architectural monuments". Academy of Sciences of the Kirghiz SSR. Institute of History. Ilim Publishing House. Frunze, 1985.

Color photographs by:

Alexander Petrov.

Authority and photos:

Alexander Petrov.