You are here

Nomadic life of Kazakhs.

Nomadic of Kazakhstan.

"The girl is alone again

Leads the caravan

And he leads

Thirty bunks - all yellow!

You haven't seen these yourself!

The copper of the muzzles is like heat,

Dried silk - reasons,

And under it the bunk itself -

More beautiful than all, mighty and fierce!

And herself, she herself -

Like the full moon

Like a silver carp

Playing out in the water

She bends her flexible figure."

Kyz-Zhibek is a Kazakh folk lyric-epic poem.

Nomadic Kazakhs.

In the nomadic life of the Kazakhs, the aul represented a group of yurts, united along economic and family lines. The aul had its own permanent tracts for nomadism: kokteu - spring, zhaylya - summer, kuzeu - autumn and kstau - winter, where wooden and clay buildings were built.

These tracts were assigned to a given village by agreement between the elders of the clans and were a constant cause of discord between individual villages and entire clans. The owner of the aul was a wealthy person, the head of the family, bai or elder, and the aul was called by his name.

His “Big Yurt” was placed on the edge of the village, behind it in an arc there were o ta u (“Young Yurts”) of married sons, then close relatives, special “Lounge Yurts” for visitors and then - the yurts of “neighbors” serving the village.

On this edge of the aul, a kotai was set up - an open corral for sheep, zheli - a tether for foals, yurts were set up for making cheese, etc. The sons and closest relatives of the owner of the aul roamed with him until the population of the aul herd did not exceed the established number, when common watering, grazing and caring for livestock became inconvenient (for example, you cannot keep more than a thousand sheep in a flock).

Then the family members separated from the father’s “Big Village” with their livestock, yurts and “neighbors,” forming a new independent village, nomadic and wintering separately, but usually in the neighborhood. All household work in the village was carried out by “neighbors” - poor relatives or farm laborers who received payment in kind in the form of a share of milk yield, wool, a stipulated number of heads of livestock for slaughter: herdsmen, shepherds, shepherds, milkers, cooks, water carriers, etc.

The poorest part “neighbors” - the harvester - did not go with the village on a seasonal migration, remaining in the wintering quarters to guard the buildings. All the rich exploited the labor of the Zhatak - the most disadvantaged part of the steppe population of the late Middle Ages, forced to settle for lack of their own livestock.

The Zhataki, literally “lying”, were engaged in the construction and repair of winter camps - kystau, with their residential and outbuildings, the preparation of hay for the Bai cattle, which was not always enough for the winter, and primitive agriculture in river backwaters, around fresh lakes.

The entire wealth of the Jatak consisted, as a rule, of one or two dairy cows, a camel and a horse for draft power. He had almost no sheep or goats. “The nomadic steppe dweller eats, drinks and dresses in cattle,” Chokan Valikhanov once wrote, “for him, cattle is more valuable than his peace of mind.

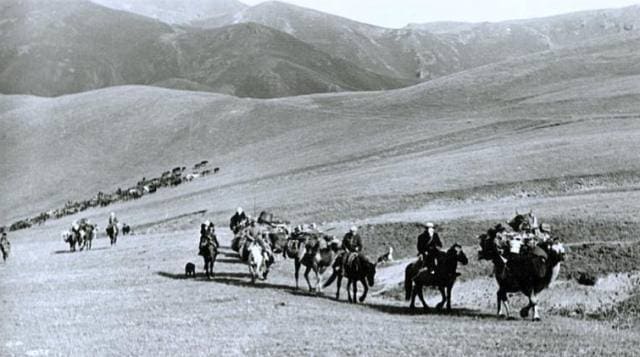

They usually roamed in an aul - a mobile village connected by family ties or economic benefits, adhering to the same tracts and wells in order to avoid clashes with neighbors. In tracts with an abundance of grass and a good watering hole, the aul was located for several days, and if conditions permitted, even more. In deserted deserts with sparse grass, stops were reduced to 2 - 3 days.

This type of nomadism among the Kazakhs is considered to be “meridian”, i.e. from south to north and from north to south. For the Kazakhs of the senior zhuz, the foothills and mountains of Altai, Tarbagatai, Dzungarian, Trans-Ili and Talas Alatau served as summer nomads.

They usually wintered in the sands of Moiynkum, Sary-Ishik-Atrau, mountain valleys protected from cold winds, wherever there was not much snow and livestock could get food. In the spring, gradually rising into the mountains, the nomads brought their herds to the alpine meadows, where the cattle remained all summer.

By autumn, all the herds were brought down again. This is the so-called. “vertical” nomadism, with its somewhat less extended transitions compared to “meridian” ones. The third, the so-called “wintering” (stationary) nomadism, was typical for the arid regions of southern Kazakhstan.

The nomadic herders spent the winter in villages located in areas of irrigated agriculture, where their estates were located with insignificant. Supply of hay so that they could keep a small number of livestock with them. And the main herds wintered in tugai, reed thickets of the floodplain of the Syr Darya, Talas, Chu, where the animals could obtain food themselves. In the spring, wealthier pastoralists traveled with their herds short distances on both sides of the Syr Darya, along the Karatau ridge, Talas Alatau, Ugam, settling for the summer near lakes and wells, and returning to winter lands in late autumn.

The distance to the summer camps was within 40 - 50 kilometers. All types of Kazakh nomadism were characterized by their own species composition of livestock. Under the “meridian” system of nomadism, the herd included many sheep, horses, and camels, especially two-humped camels, which were capable of roaming, i.e., independently obtaining food and facing the difficulties of a long journey.

Under the “vertical” system, cows were added to sheep and horses, and under the “wintering” system, both animals were added, but only in limited quantities. Consecutive movement across seasonal pastures was a single production process, in which migration acted as a stage of its closed annual cycle.

Despite the difficulties of the transition, summer migrations are the best thing that a steppe dweller could experience in life, when livestock quickly gains weight on summer grazing, you can enjoy fresh meat, milk and kumiss, and spend a carefree few months in the clean air under the open sky.

This is also the time for weddings, competitions in songs, agility, and strength. And therefore, the generous summer with its colorful journeys is sung in songs, the epic poem “Kyz-Zhibek” with all the colors of versification.

In all likelihood, it was from those distant times that the Kazakhs retained the tradition of lovingly decorating a loaded camel with carpets, for which blankets with embroidery and all kinds of pendants were specially made.

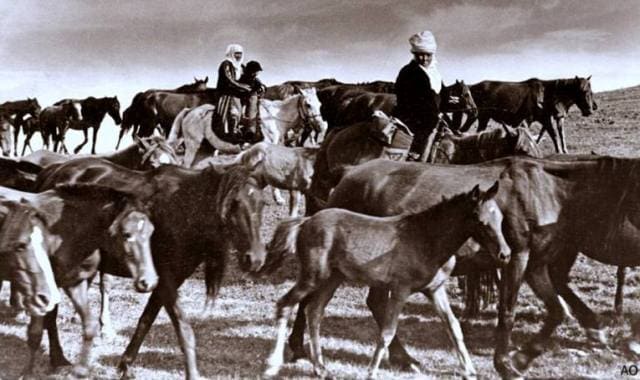

A caravan of loaded camels was usually led by a girl in a rich outfit on a pacer horse or on a leading camel - a bunk. In the summer, the Kazakh ulus wanders to all places, and these steppes are necessary for the preservation of their extremely numerous livestock.

During the summer, they travel this road around the entire steppe and return. Each aul stands in some part of the steppe on a place that belongs to it; They live in yurts and raise animals such as horses, sheep and cattle.

From their ancestors - nomadic tribes and peoples who inhabited the expanses of Eurasia - the Kazakhs inherited the yurt. This portable dwelling in its design is most consistent with the nomadic way of life, and in its artistic design it has no equal.

Yurts in different parts of Kazakhstan differ somewhat, mainly in the shape of the dome. In the south, the dome of the yurt is higher and steeper; in the north, in steppe Kazakhstan, it is more flat. Setting up and dismantling the yurt, the hassle of arranging and loading utensils is the work of women; only the heavy shanyrak rim is lifted by a man.

Previously, the yurt was transported in a pack on camels or bulls; later, carts were also used for this. In most regions of Kazakhstan, a yurt is called kiiz uy, which means “felt house”, but also “agash uy” (“wooden house”, Western Kazakhstan), “Kazak uy” (rarely).

Being skilled cattle breeders, the Kazakhs over the centuries have developed a rational way of alternating pastures and established a convenient procedure for grazing livestock. The entire grazing territory was divided into four, according to the seasons, types of pastures: Kystau, Kokteu, Zhailau, Kuzeu.

Migrations - koshes were mainly carried out in the direction from south to north and back, and in the mountainous regions a vertical system of nomadism was practiced: summer camps (zhailau) were located in alpine meadows, and winter pastures (kystau) in the foothills.

Sometimes the journey made by migrations was very long and reached 800 - 1200 km in one direction. The stopping places of the most powerful and numerous clans were always located in a certain territory, and no one dared to encroach on their nomadic paths.

During the harsh winter, winter pastures were depleted, livestock was exhausted by a half-starved existence. Therefore, the migration to spring pastures was especially joyful: girls dressed in festive clothes rode in front of the caravan.

Horse patrols were sent ahead to check the condition of the pastures, choose the best ways to reach them, and mark out camp sites. But the most important and responsible period was the stay on the summer nomads, on which the feeding of livestock and its preparation for the hard winter depended.

Nomadic routes were organized in such a way that they passed through convenient passes, territories rich in food, equipped with good watering places, in the absence of which wells were dug. The traditional diet of the Kazakhs clearly reflects the established way of life of the nomadic society.

The basis of nutrition was dairy, meat and, partly, flour and cereal products. They used milk from various domestic animals, and never consumed it fresh. With the onset of autumn, when animals stopped milking, meat and, to a certain extent, plant foods began to predominate.

In the summer, when the bulk of the livestock was driven to separate pastures for dairy sheep They grazed them near the village and milked them twice a day. On the summer pastures, the selection of male sires and the first shearing of lambs were carried out, the wool of which was used to make felt.

Women were engaged in spinning and making clothes, dressing hides, and preparing dairy products. Sheep were sheared in the autumn pastures, after which they began felting, repairing tools, storing fuel, which served as dung - tezek and kyi - ki, and preparing homes for winter.

Before being sent to winter pastures, livestock was mass-slaughtered for meat: Sogym. The first greeting of a Kyrgyz begins with the following phrase: “Are your cattle and your family healthy?” This care with which one inquires about the cattle in advance characterizes (it) more than entire pages (of descriptions).”

And the well-being of livestock - the main wealth of the steppe inhabitants - depended entirely on natural conditions, in accordance with which seasonal pastures historically developed. The northern forest-steppe and southeastern mountainous regions of Kazakhstan, where significant amounts of precipitation fell, were used mainly for summer pastures - dzhailyau (zhailau), while the eastern and central ones were used for winter pastures - kys-tau.

But the spring - Kokteu and autumn - Kuzeu pastures were directly adjacent to the wintering areas. Seasonal pastures, although traditionally distributed among clans, were, with the exception of winter ones, for common use.

The Kazakhs are characterized by all types of nomadism known in history - the so-called “meridian”, “vertical”, “wintering”, determined primarily by the number of livestock on the farms, the natural and climatic conditions in which certain groups of nomadic pastoralists were located. Nomads and semi-nomads had their own separate winter camps, with protected areas for grazing young and weak animals.

They were called koryk or koi bolik. More independent cattle owners also had spare wintering quarters - kelte kystau, zhalgan kora and part of their livestock were kept in stalls in the winter. The summer nomads of the Kazakhs of the Middle and Junior Zhuzes were in the forest-steppe and steppe zone of Sary-Arka, the winter ones - in the floodplains of the Syrdarya, the lower reaches of the Chu, at the foot of the Karatau, in the Aral Sea region, and on Mangyshlak.

In early spring, following the advancing warmth, the nomads began to move north. The Kazakhs of the southern part of the Sary-Arka steppes, who not only in summer but also in winter led a nomadic lifestyle in the lower reaches of the Chu, walked only in one direction up to a thousand kilometers from the Chu River, through Betpak-Dala, the Ulytau Mountains to the present Atbasar.

The nomadic population of the right bank of the Syr Darya moved north through the Karakum, Ainakul to Turgai and further to Kustanai. From the Ustyurt and Mangyshlak plateaus, the lower reaches of the Urals, the banks of Uyul, Sagyz, Irgiz, where there was a lack of summer pastures, people migrated over the summer to the boundaries of the present-day Ural, Aktobe and Kustanai regions, covering more than a thousand kilometers in one direction.

However, many farms moved within their ancestral lands. And low-capacity farms or impoverished populations remained in winter camps. The number of such farms at the beginning of the 20th century. was quite large even in such purely nomadic pastoral areas as Mangyshlak and Ustyurt, the lower reaches of the Syr Darya.

Thus, numerous herds of cattle of the Kazakhs of the middle and junior zhuzes were in the Ishim, Turgai, Tobolsk, Ural and Aktobe pastures in the summer. And with the approach of autumn, following the retreating heat, they moved back to the south, to their wintering places. The routes of such migrations were regulated primarily by the location of water sources.

Authority:

The book “Kazakh traditional culture in the collections of the Kunstkamera”. Almaty, 20808. Uzbekali Janibekov.

Photos by

with the permission of Almas Baimukanuly Ordabaev. From the family archive.